Recently I realized, not for the first time, that moving “house” and moving “home” are two different (though interconnected) things. Moving house is concerned with stuff; moving home is transplanting something intangible. For me, home was the one that mattered most. While downsizing and packing I was thinking about the difference, and I asked myself: “Where, in all of this, is home? What is home?” I wanted to pay attention to it before dismantling it, afraid that once I had taken it apart I’d no longer be able to analyze it, to see and feel it, to focus on it – and eventually to recreate it.

Because I live alone the process has been different for me than it would be for a couple or a family. Moreover, the fact that I’m in my eighties and was moving from a house to an apartment in a seniors’ building gave the process a valedictory element: this was downsizing into extreme old age, packing as much as possible into the lifeboat. Since there is security in “home” I needed to hold on to as much of it as I could.

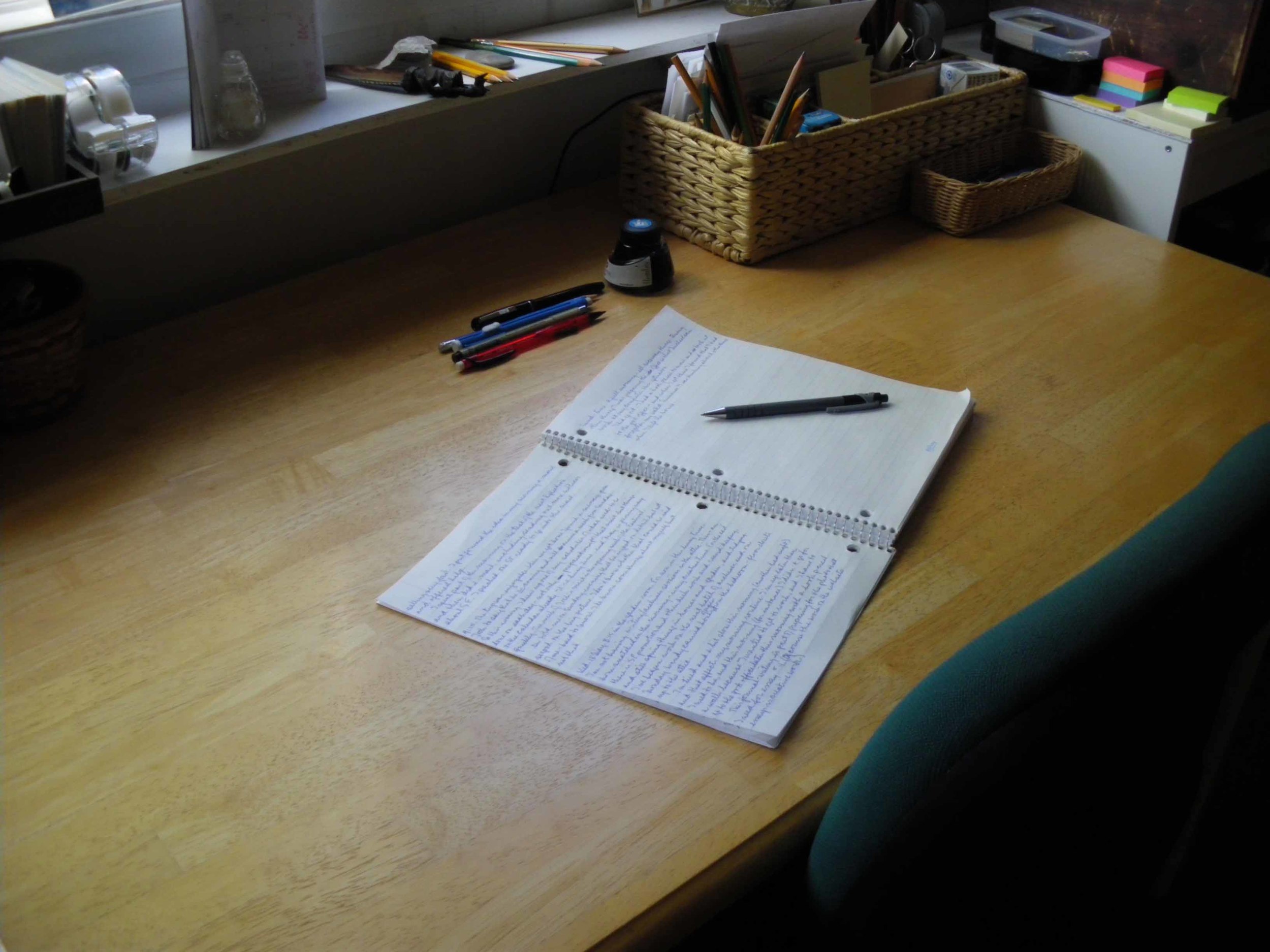

As I approached the move, and to assist with the transplanting, I made notes about where I was with various strands of my life and activities – something like the interruption notes that I make when I have to break off a writing project, so that when I return to it I will be able to pick it up as quickly as possible. The process of making notes helped me to notice, to pay attention.

”Home” is an elusive concept but I’ve been able to pinpoint a few things. It’s not only in my belongings themselves but in the way they relate to each other, the web among them: the arrangement of writing equipment on my desk, of the familiar objects along the back of the kitchen counter. The importance of the arrangement raises the question of whether disposing of some belongings damages the whole “home.” Yes, it does, though what’s left can probably, like a pruned tree, heal itself and be whole again, though different.

Home is also in the way I use and live among my belongings, in how I move among them. It’s in the routines and habits – patterns in time and space – that make up the tapestry of my life. I notice the choreography of how I prepare my breakfast: reaching for things, doing things in a familiar sequence.

While dismantling I realized that in my living space there are “hubs”: my reading chair, my writing places, my bedroom. I’ve tried to transplant them so that they’re as much as possible the way they were. I like my reading chair to have its back to a wall or a corner. The lamp beside my desk has to cast its light just so. Everywhere – bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, as well as study and living room – I need writing materials.

Home is partly in activities, in the texture of daily life. In this new setting I’ve had to reconstruct whole chunks of the daily routine. Some of it I could transplant, moving the familiar and comfortable into a new frame, but much of it I had to reinvent.

Home is, of course, among friends and family, and in the objects and activities associated with them. It’s in the neighbourhood and its people, their comings and goings – again a mesh of movements of which, while living in the house, I was a part.

So, having dismantled, and having packed and unpacked, how am I doing with the process of recreating home? For a start, there are days when I feel, despairingly, that it has been impossible to move it. Many components simply can’t be moved. The neighbourhood, of course. The view from the windows: trees and garden, the company of birds and squirrels (squirrels don’t visit my fifth-floor balcony). The angle and intensity of the light at different times of day. The fireplace and the shady porch. The fabric of an old and well-used house. The reconstructing is taking place in an entirely different framework.

But fortunately there are better days, when I notice that I’m gradually starting to feel the new structure taking shape around me. The new arrangements of belongings are becoming familiar; some of the new routines are almost automatic. I no longer have to think about where I put the stapler or the granola. I no longer have to think out the early-morning or the bed-time routines, or the arrangements for washing the dishes in an entirely different kitchen. Many things are in the right places: the books are not yet completely organized the way I want them to be, but if I want a particular book I at least know which shelf to go to. I know where to look for things in the kitchen, the storage room, the study. It’s nowhere near complete but it’s happening and I have the feeling of … well, if this were a house that I was building I’d say that the floor and the studs of the walls are in place, and some of the walls are filled in; the roof is partly finished. It is now at least a partial shelter. It will be different but it will be another version of “home.”