A few years ago, the Google street-view of my street showed me standing beside my car, locking or unlocking it. It was an unimportant episode in one of my days, but it gave a glimpse of a moment in time: that moment, that spot on the surface of the planet.

Sometimes, even without Google’s help, a moment in time is suddenly and unexpectedly illuminated. More than three and a half million years ago, three people walked across a patch of wet volcanic ash in what is now Laetoli, Tanzania. The tracks they made were covered by another layer of ash and hidden until they were found in 1978 by Paul Abell and Mary Leakey. The tracks were important because they put the date for human bipedalism – two-footed walking – quite a lot earlier than it had, until then, been set at, and they showed that those very early humans walked pretty much the way we do today. Those three people, out on their daily errands, perhaps to find food or fetch water or look for a strayed child, were unaware that the tracks they left would one day be of enormous significance for understanding the evolution of the human race.

There was another such moment about 5,000 years ago. In what is now northern Italy, a middle-aged man walked from the valley where he lived up into the Alps. It was autumn, and at the altitude that he reached it was snowing. He had probably been hurt in a fight (four of his ribs had been broken quite recently), and he may have been escaping from whatever dangerous situation had led to that injury. In pain, probably exhausted, he took shelter in a small gully. He lay down to rest, and he died. He is now the famous “man in the ice”, and his body and equipment have provided invaluable insight into the life of the Late Neolithic. As with the Laetoli footprints, a moment in time was preserved because the physical conditions of the time and place were precisely right.

Most of the moments of which history is composed are unrecorded and unimportant. Large-scale historical narratives that give the big picture are essential to an understanding of the past, but the big picture is made up of moments (think of pixels). I reflect on the person who looked at a container of curdled milk (“Spoiled! What am I going to do with it?”) and took a step – whatever it was – in the direction of turning it into cheese. Or of someone who, talking to a neighbour, said something like, “My mother always threw away the peel of this fruit but I’ve found that when I chew it it cures the stomach ache.”

Where we are now – the planet and its inhabitants – is the result of an accumulation of such moments. Our understanding of the past, besides being about the big picture, is about the specific and local. Part of the study of history and the process of making it accessible is concerned with this “specific and local.” We see something like it in pioneer villages and in the historical writing that begins with a single specific event and traces what led to it. It appears in the kind of historical fiction that presents the lives of characters who, even if imaginary, are based on research and the informed imagination, the kind of book that allows the modern reader to get a glimpse of what it would feel like to live then.

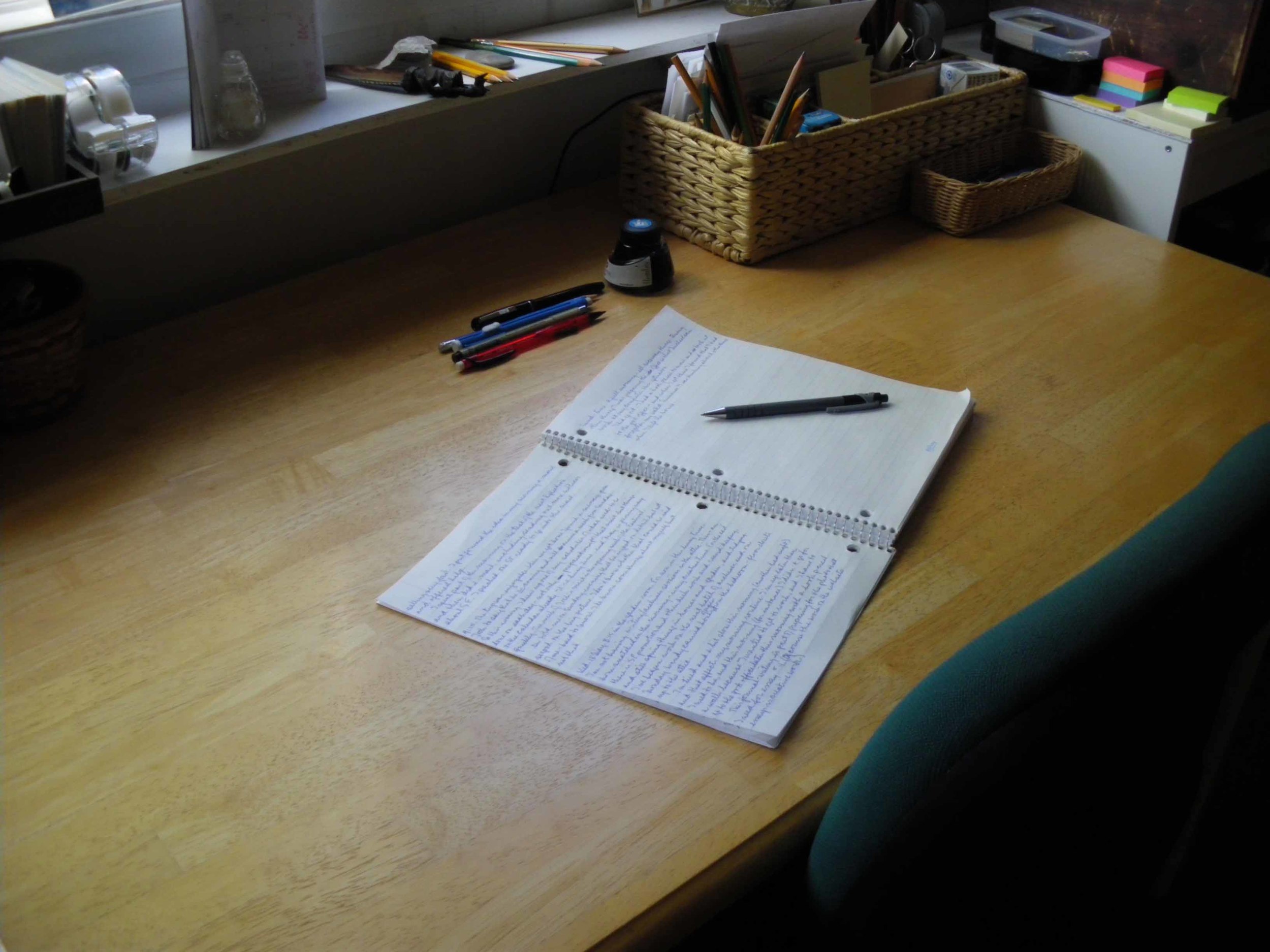

Those of us who write journals or diaries add to the historical record each time we write an entry: diaries and letters written in the past are precious sources of information. They are the way in which we leave tracks. Each entry is the record of a moment in time, a note about where the writer – living in the mesh of personal and public events – is on that day. We, when we’re writing our journals, have no idea what will matter to future historians: one of my examples, when I was researching history for the books I’ve written, was the question of what people in historical times ate for breakfast. Almost no one ever recorded such a detail, but for what I was doing I needed to know it.

Moment by moment is how history – the big picture – is created, and it’s how we live. We, right now (I at the computer, you reading this), are at the very leading edge; we’re part of history as it’s being made.

Sources:

Information about the Laetoli footprints came from Internet sources, mainly a publication from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, and information about the Stone Age body in the Alps from Konrad Spindler, The Man in the Ice (original publication © 1993, English translation © 1994).

© Marianne Brandis, 2016.